Lowercase ea: What it is and why it matters

The first thing I want you to recognize is this: you already have an enterprise architecture (ea), whether you designed it that way or not.

The real question is whether it emerged through many unconnected decisions over time, or if it was shaped intentionally – with shared direction and follow-through.

To explore this, we need a common understanding of the words we’re using. For that, I turn to the simplest authority we all share: the dictionary.

What does "architecture" mean?

Merriam-Webster offers several definitions of architecture and my reaction to all of them was a resounding "YES!" when I first read them.

- The art or science of building

- Formation resulting from or as if from a conscious act

- A unifying or coherent form

- Architectural product or work

- A method or style of building

- The manner in which the components in a system are organized and integrated

Every one of these applies beautifully to the systems we build in organizations. Instead of walking through them one by one, I want to show you how the ideas behind these definitions come together.

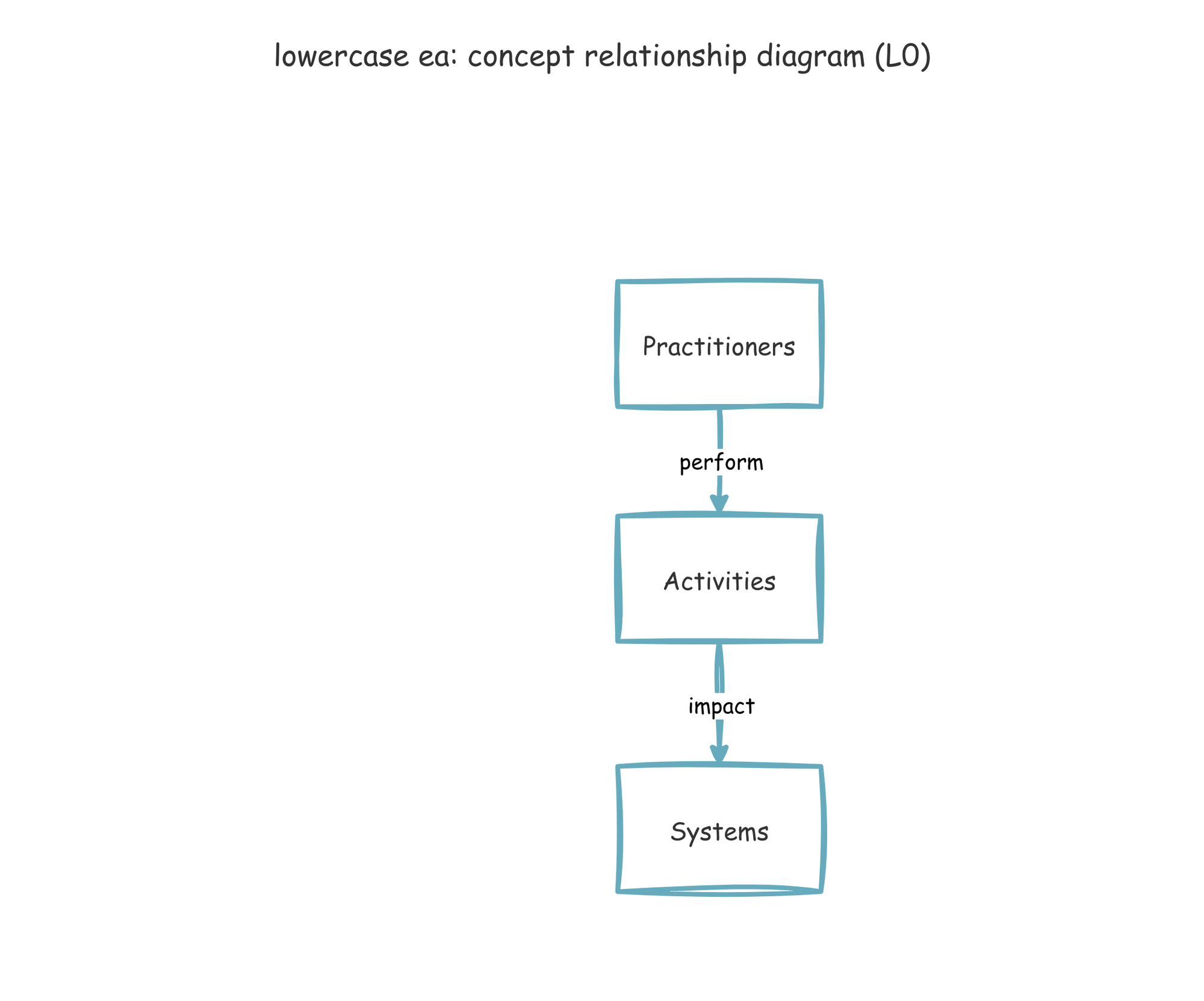

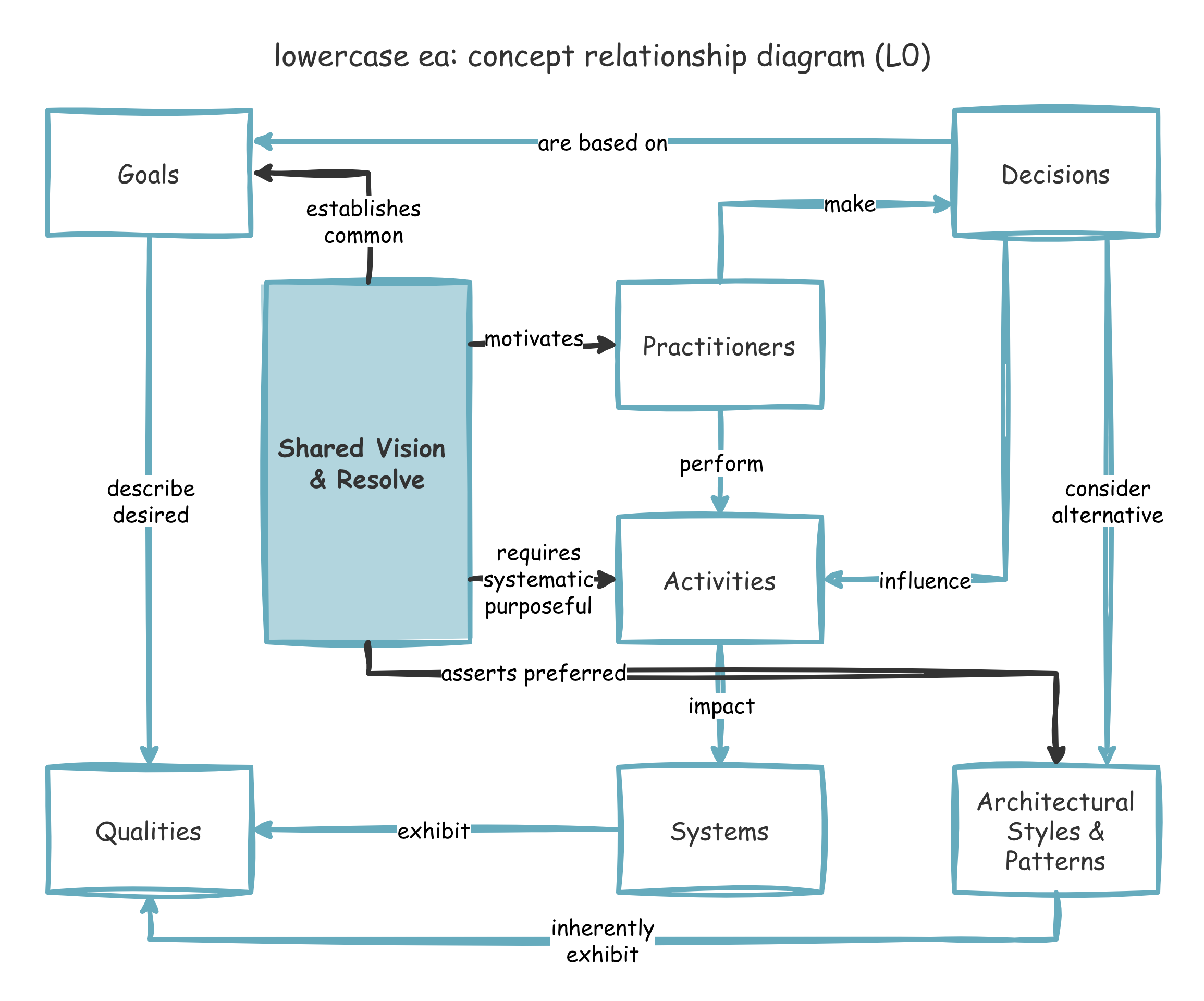

We’ll build a simple, high-level (Level 0 or L0) concept relationship diagram to align on the basics before getting into nuance.

1. People build systems

In your organization, many people contribute to the systems you rely on: architects, engineers, product owners, business partners, analysts, and more.

All of them are practicing the art and science of building solutions. In this diagram, these appear as Practitioners doing Activities impacting Systems.

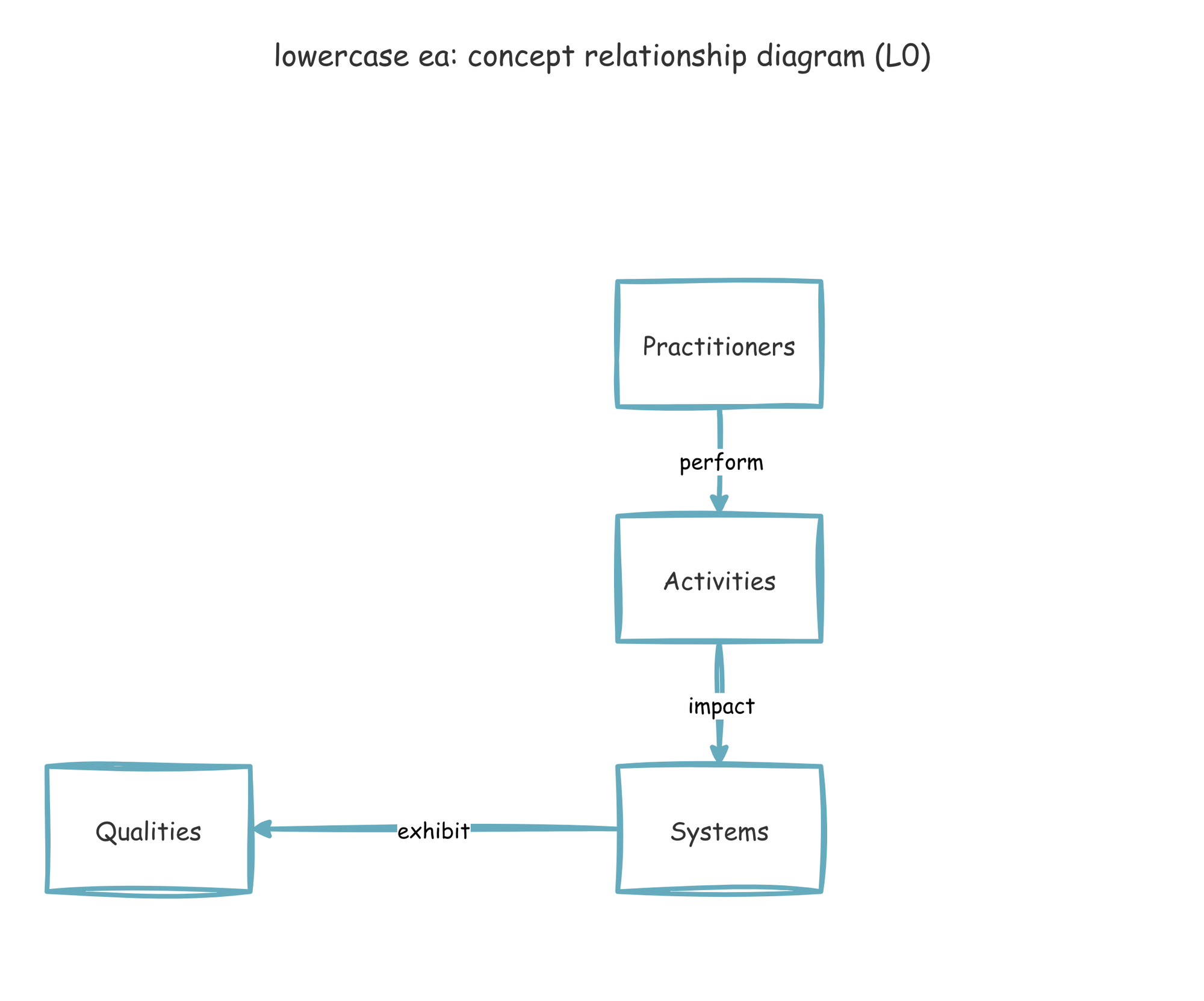

2. Systems have qualities we care about

Part of the "art and science" is deciding which qualities matter. Some are functional (what the system does), others are non-functional (how it performs). These qualities influence how components are organized and integrated. In the diagram, these show up as Qualities that shape what we build.

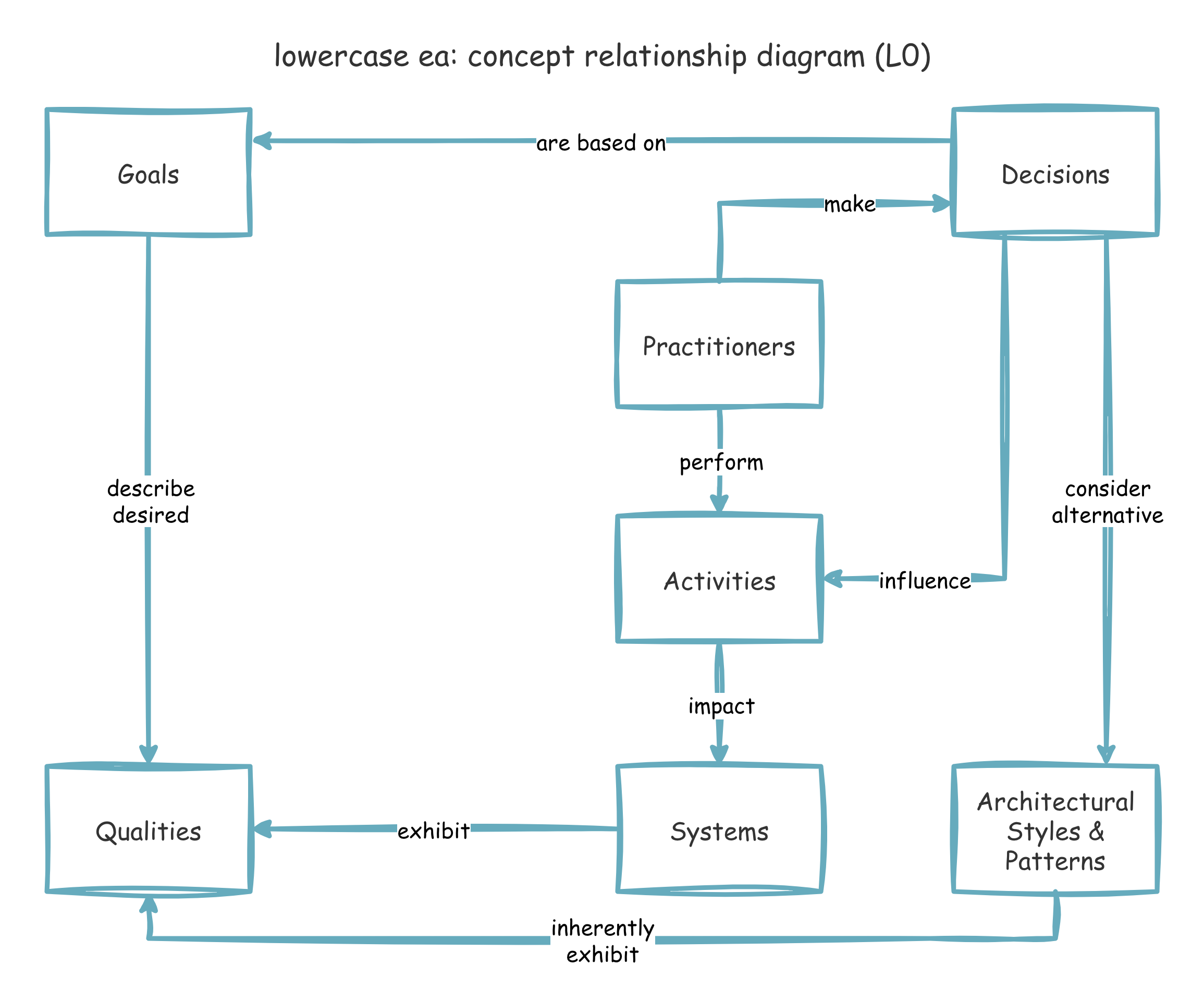

3. Decisions shape everything

Every day, practitioners make decisions – large and small – that directly affect the systems they build. These decisions use:

- Desired Qualities as Goals

- Architectural Styles & Patterns

- Constraints and tradeoffs

These decisions determine both what is intended and what actually emerges.

4. When decisions aren't aligned, dissonance grows

Without a conscious act to create unifying and coherent systems, each team’s decisions can drift in their own direction. Goals diverge, styles mismatch, and preferences quietly collide.

This produces dissonance, integration friction, and fragmented systems.

In other words:

This is your architecture.

A system resulting from many isolated conscious acts, presenting “as if” it came from a shared plan.

What can "enterprise" offer?

Merriam-Webster again invokes a resounding "YES!" from me.

- An undertaking that is especially difficult, complicated, or risky

- The full scope of an organization

- Requiring systematic purposeful activity

- Readiness to engage in daring or difficult action

Put simply:

Enterprise = the whole organization acting with shared purpose

These definitions reveal what's missing from our diagram:

5. Shared goals, practices and commitment make the difference

The way to avoid the dissonance is through shared vision and resolve – the ultimate conscious act. It will require:

- Establishing shared Goals

- Creating the systematic purposeful Activities that support the strategy

- Asserting preferred Architectural Styles and Patterns

- Motivating Practitioners to rally around the cause

This work will be difficult and complicated. If it were simple, you would have done it already. Aligning on shared architecture goals is hard; staying aligned as conditions change is even harder.

Organizations that create systematic, purposeful activities are better able to sustain momentum over time, adjust to new contexts, and prevent abandoned work from piling into anchors they can’t shed.

Why caring for your enterprise architecture feels daunting

Here is the part that might stretch your brain a bit:

To change your architecture, you need to architect the change.

You must consider and design the shifts required across:

- People

- Processes

- Data

- Applications

- Technology

These are interdependent subsystems, much like the components of any strategic business initiative.

Think about that: you're not just changing the system.

You're changing the system that changes the system.

(And yes: cut those anchors.)

Lowercase enterprise architecture: putting it all together

Here’s what enterprise architecture really is – the architecture you have, not a team you hire:

Enterprise architecture encompasses the vision, practices, and state of the systems that make up an organization's technology ecosystem. These systems evolve through the art and science of building solutions – done across many teams, with different skills and perspectives.

Organizations that commit to a shared strategy – and intentionally design the activities that support it – can create unified and coherent systems that meet business needs as they evolve.

It's difficult work – but organizations ready to engage in these challenging, purposeful actions will succeed.

This is lowercase ea.

You don't need an uppercase EA team to have it.

(But a good one can help create the common ground and momentum to make it easier. More on that soon.)

Reflection

Before you move on, pause for a moment:

Are you approaching your enterprise architecture with a shared strategy – and designing supporting activities necessary to make it real?

If not, what would be different if you did?

References

Have questions or thoughts about this post?

Email me at hello@eaforeveryone.com or connect with me on LinkedIn.